Almost six months after the start of lockdown in Europe, we still have no clear answer to the psalmist’s question, ‘How long, Lord?’ (Ps. 13).

A matter of weeks, we first thought; then conceded that it could take months before ‘normality’ would return. Now we hear it could be years before we return to our pre-corona lifestyle of world travel, hugging friends and relatives, singing in church, yelling at football matches and crowding into restaurants, cafes and bars… if ever.

Far from ‘disappearing with the spring’, the pandemic continues to produce more questions than answers. Will vaccines be available soon? Will vaccine-phobia make group-immunity impossible? Will global air traffic ever recover? What will the long-term effect be on families? on marriages? on a generation of children whose education has been disrupted? When will my wife and I be able to use the travel vouchers received last week for a cancelled trip to New Zealand to see my 97-year old mother?

How long, Lord? Half a year on, no-one really knows.

In the first weeks of lockdown, I circulated a far-sighted article from the Praxis Journal to friends and colleagues called: Leading Beyond the Blizzard. While incompetent political leaders were playing down the seriousness of the crisis by disparaging experts and professionals, these authors urged their readers to recognise COVID-19 not just as something to ‘get through’ for a few days or weeks. Rather, we were facing at least an economic and cultural blizzard. Yes, survival would mean bunkering down for the coming weeks, but more likely, this was the start of a long harsh winter requiring a total re-think of operations. Very possibly, we were on the brink of a ‘little ice age’ — a once-in-a-lifetime change upending our lives and organisations for years to come.

We’re not going back to normal, the authors warned, quoting an MIT Technology Review article predicting that social distancing was here to stay for a long time. The COVID-19 crisis could only end either when a vaccine was available (and applied) or when enough of the world’s population (two-thirds?) had become infected and thus immune(?); with enormous human and economic costs.

Yet this pandemic is probably not ‘The Big One’, according to Michael Osterholm and Mark Olshaker in their book, Deadliest enemy (2017), which included a chapter on coronaviruses titled ‘SARS and MERS: Harbingers of Things to Come’. ‘Terrible as it is, COVID-19 should serve as a warning of how much worse a pandemic could be’, write the authors in the July/August Foreign Affairs magazine.

So what lessons should we be learning from this pandemic?

Firstly, we should prepare for much worse realities, sooner or later. Globally less than one million have died from COVID-19, one-fifth being Americans. Yet the 1918 influenza pandemic took 100 millions lives, equivalent to 400 million today. Still, the likelihood of better preparation in the future is low. As one former White House staffer observed, leaders ‘do what is easy and pays immediate dividends rather than what is hard, where the dividends seem remote.’ This is not new: Daniel Defoe wrote in 1665 that London authorities first tried to ignore the Bubonic Plague, keeping information from the public until the spike in deaths became undeniable.

Secondly, we should remain focussed on our mission in our local churches and mission organisations – not on preserving our past means and methods for pursuing that mission. This is a time to re-evaluate everything. Ask what God might want us to do differently. Be alert for new opportunities new challenges bring, trusting in God’s sovereignty. We can be thankful for the internet enabling families, friends and fellowships to connect like never before in history.

Will the post-corona church look more like the home fellowships of the early church, not centred on the large buildings and formal ceremonies of Constantianism?

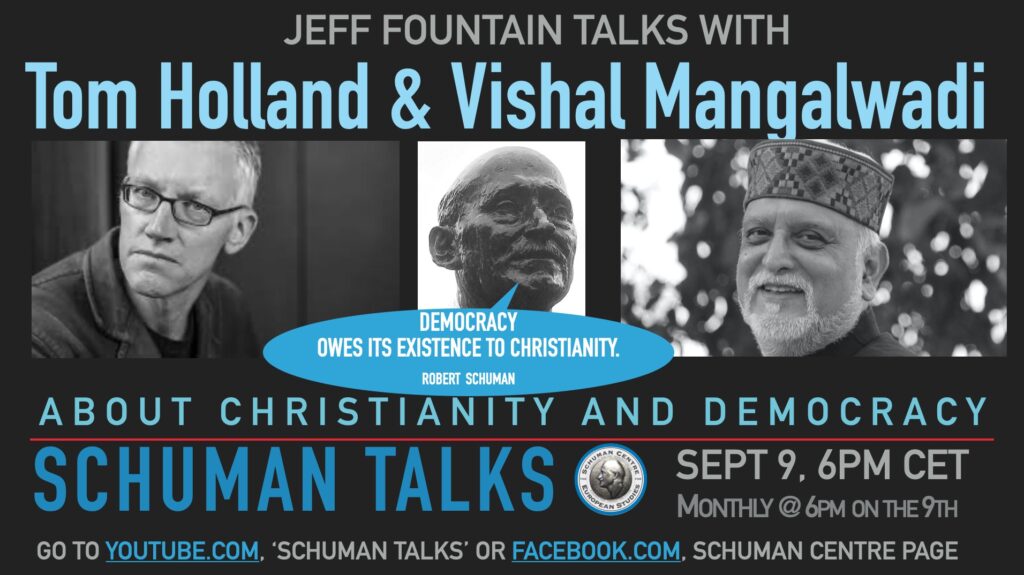

What might a post-corona Youth With A Mission look like, having developed short term missions in the jet-age with global travel, and international schools and outreaches, all of which are now greatly restricted? One of the YWAM values is ‘doing new things in new ways’. The crisis catalysed new ways to pursue our Schuman Centre programmes this summer: an online State of Europe Forum, spawning monthly online Schuman Talks; online Continental and Celtic Heritage Tours with global participation; a hybrid Summer School in European Studies with participants both in the Amsterdam classroom and around the world.

Thirdly, we should heed Peter’s warning ‘not to be surprised at the fiery trials you are going through’ (I Peter 4:12). He would have agreed with Paul that ’neither death nor life … nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord’ (Romans 8:38,39).

With the psalmist, whose question remains unanswered, we can also say: I will sing the LORD’s praise, for he has been good to me. (Ps. 13:6).